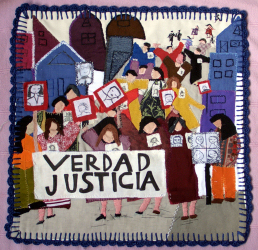

Memory initiatives have served several purposes: to recover the memory of what happened and make public denunciations, dignity and honor the memory of the victims, promote community organization and social reconstruction, inform and educate new generations, and to demand redress and justice. This paper focus on Guatemalan murals as a memory initiative and as an art form used by the direct victims of the conflict.

All posts by danielavalero

THE MURALS IN GUATEMALA AS A MEMORY AND RESISTENCE INITIATIVE

Memory initiatives have served several purposes: to recover the memory of what happened and make public denunciations, dignity and honor the memory of the victims, promote community organization and social reconstruction, inform and educate new generations, and to demand redress and justice.

http://prezi.com/9x-yrgkcjv2v/?utm_campaign=share&utm_medium=copy

EL BAILE ROJO

El Baile Rojo, documentary about political genocide in Colombia a documentary about a political party in Colombia called the Patriotic Union (Union Patriotica). About 4000 of its members where killed in a genocide managed by politicians, paramilitaries and militaries in a plan cinically called “the red dance” under the Condor Operation.

Spanish link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pwgudt5l0ZY

English link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AMQng34vHJc

UPDATE PROJECT INVESTIGATION

Taking into account the comments received, this research will have two areas of focus. The first is to know the range of victimization that the conflict in Guatemala generated, and establish the extent of victimization are located some of the Guatemalan artists who have devoted much of their work to keep the memory of what happened.

The second focus, which follows from the first, is to identify those artistic initiatives arising from local communities who are direct victims of the conflict. The idea is to know what kind of initiatives have created, what kind of narrative have chosen, what impact it has had. A not Guatemalan example of this type of art is the community of San Carlos, Colombia, the community created a play that tells the story of what happened in his town, from conflict to reconciliation with armed groups this in order to forgive but not forget.

These are some cases I’ve found that may be helpful:

Escuela de Arte y Taller Abierto de Perquin

Sergio Ramirez (in exploration)

Kamin (in exploration)

These are some of the academic readings that may be relevant:

Politics in art and art in politics

To reflect the soul of a people: the Guatemalan art

Maurice Halbwachs. From on collective memory. The collective memory reader.

Joshua Hirsch. Post-Traumatic cinema and the holocaust documentary. Trauma and cinema

Jehanne-Marie Gavarini. Rewind: the will to remember, the will to forget.

ARTICLES FOR WORKSHOP

OPERACION MARTILLO (OPERATION HAMMER)

Guatemala-U.S. Drug Operation

“Rural communities in Guatemala are fearful of the military being used to combat drug traffickers because the same techniques are applied that were used in contra (counterinsurgency) warfare,” said rights advocate Helen Mack, executive director of the Myrna Mack Foundation. “The historical memory is there and Guatemalans are fearful of that.”

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/09/01/guatemala-us-drug-operation_n_1848731.html

http://www.insightcrime.org/news-analysis/marines-deployed-guatemala-zetas

The Voice of the Voiceless- Project Proposal

During the decade of the 70’s and 80’s, Latin America had a period of conflict, military dictatorships, and clashes between left and right ending with: massacres, forced disappearance, forced displacement, sexual violence, homicides, genocide, torture, etc. Years after their processes of transition from war to peace and from dictatorship to democracy, the victims of these unfortunate events still struggle to make a memory, and not to leave in the past what happened, because even after 40 years of violence, people do not recognize what happened, because they consider it oblivious.

Latin America is in a struggle for collective memory and impunity resents its past; there are still difficulties to understand the complexity of the experiences, motivations and consequences of the repression experienced. One of the tools used for collective remembrance is art, art understood as a memory tool and denunciation against impunity, which has been used before, during and after the period of repression.

Those who make this art, I understand and analyze them in two different groups. The outsiders artists, who are committed to collective remembrance and denunciation of human rights violation, but who are not direct victims of repression and conflict; these artists, know well what happen in their country, they understand the suffering of their people, but have not experienced the conflict or the violence by first hand. On the other side are the insiders artists, in this case I understand them as the direct victims of the conflict and repression, who through the arts express not only a claim against what happened, but also their individual memory, which feeds the collective memory and reveals the truth that is being denied, a recognized example is the filmmaker Rithy Panh.

In this project I analyze the struggles for memory of local communities who have used art as a tool for collective remembrance. It is about knowing how victims of conflict expressed their specific stories and their particular views of the past. I pretend to analyze the resources chosen by the victims, how they intervene to bring attention into their project, and the kind of narratives they used: visual, theater, murals, photography, or painting.

The idea of this project is to change the view of art in the context of conflict. No one speaks of giving voice to the voiceless, is about hearing the voice of those we assume are voiceless. It is not about to show the pain of the victims through the art of others, instead is about the art made by victims who explains their own pain, their own memory.

Note: I’m not quite sure about this, but depending on the information that I find, it will be interesting to open a blog where people can find this kind of initiatives.

Outside to be Inside

From all the art works that we could appreciate in the Under the Same Sun exhibition, the one who struck me the most was Javier Tellez video Bala Perdida (One Flew over the Void). This short film try to cross the social and political boundaries in two ways. First is the most obvious one, when a human cannonball is shot over the border into the United States without a visa, we clearly understand that is a statement against boundaries and the hardships faced by millions of Latin Americans workers who cross the border illegally every year in search for better life. But there is another social and political border that Tellez crosses with this film when he documents a parade organized by local psychiatric patients, in this specific case, he show us the other as the “normal” and give an unexpected space to the unexpected people.

Javier Tellez, a Venezuelan artist who lives in New York, creates films that combines documentary with fictionalized narratives to question definitions of normality and pathology. When he is going to do an art installation, he looks first to make a collaboration work with institutionalized patients living with mental illness, to rewrite classic stories or invent their own, he creates what he calls a “cinematic passport to allow those outside to be inside”. His work is understood as a therapy that attempts to cure viewers of false assumptions, rather than the patients, he tries to build a bridge through the desestigmatisation of those who are different.

There are two main elements in Javier Tellez films. One is the use of masks as an allusion of the therapeutic potential in the change of roles. The second one, is the constant communication through boards and the dissociation of sound and image, the constant use of voice over, reminds us the voices that the patients hear.

I like Javier Tellez work because he gives voice to the voiceless, he portraits the other, the individuals that we usually don’t think about. As he said “his work is for the “normal” society, who must be cured from their fears and prejudices against those who are different”.

If you want to learn more about Javier Téllez here is an good interview about his work, is in english and spanish: http://bombmagazine.org/article/3379/javier-t-llez

Symbols of Memory and Resistance

Forced disappearance was a violent practice, which flourished in Latin America during the seventies with the arrival of military dictatorships and armed conflict. This practice was used for different purposes according to the country. For example, in some countries of Latin America, the military used it as a repressive approach, in other countries it was the right way to lower homicide rates and maintain an attenuated war.

For a while the forced disappearance seemed to be the perfect crime within its perverse logic, there are no victims and therefore no perpetrators, as well as exposes Weld “a desaparecido is neither quite dead nor alive, simultaneously present and absent” (p.8)

The constant pain that this violent practice produced on the families of the victims, and the constant wondering of “where are they?” “what happen to them?” “Did they suffer?” “For how long did they suffer?” and the special case in Argentina where the mothers of Plaza de Mayo not only wonder about their children but also about their grandchildren. Have generated a very important and interesting artistic production, I remember seeing an exhibition in Colombia on the disappeared in Latin America one of the symbols created to portrait the disappeared in Argentina and then used in some countries of Latin America as a flag, was a graffiti of a bicycle that has a number in red in one of the tires which represents one of the 350 students of Universidad de Rosario disappeared during the military dictatorship.

But there were other artistic initiatives – or at least that I consider artistic- that comes from the people, looking for not only a symbol, but also to maintain the memory of what happened and a voice of resistance. One example of this kind of art are the Arpilleras. During the dictatorship in 1974, the catholic church opened a workshop to help women victims of the violence to produce carpets so they can have some financial income. These women started to transform those usual carpets into an instrument of public denunciation of social injustice and the violation of human rights, the movement spread to other cities and other countries around the world.

These two kinds of representation and symbolism, one coming from the Artilleras and one coming from Fernando Traverso a known artist from Argentina, makes me wonder if we can consider both art? and if they are both art which of them has has a broader meaning in the collective consciousness and memory?

Daniela Valero

I graduated with a degree in political science from the Universidad de los Andes in Bogota, Colombia. There I worked as a social researcher for four years for projects related to historical memory, armed conflict, reconciliation and transitional justice at Cifras & Conceptos S.A. Additionally, provided support to the generation of proposals and projects related to the same topics, and the development of one of the chapters of the book Basta Ya, Colombia memorias de guerra y dignidad. (No More, Colombia memories of war and dignity), from the Colombian Historical Memory Group. During this period of time, I also made a short documentary, Nacho’s Path, that recieved a Honorable Mention in 2011 Waste pickers and Recyclers Project Social Documentary Competition, and was part of the official selection at the IX Festival Internacional de Cortometrajes y Escuelas de Cine El Espejo (IX International Festival of Short Films and Film School The Mirror).

One year ago I decided it was time for a change of scenery, so I move to New York and enrolled in the Certificate of Documentary Studies and later into the MA in Media Studies to learn how to make and use documentaries to uncover the stories that remain hidden in remote and conflicted places, and get people involved and aware of the reality.

Documentaries on Guatemala

Here are the links of the three documentaries, the last one is in Spanish I couldn’t find the English version:

Nostalgia for the Light: https://vimeo.com/72022198

When the Mountains Tremble: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a4rG8nmgRw4

Granito: How to Nail a Dictator i(n spanish): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n3P6zBcLTjE